As both an academic and a professional writer you have published research papers, a doctoral thesis, poems in anthologies, and most recently your own poetry collection, Biometrical. Is there a writing schedule or any particular writing habits that help you to be so prolific? Many writers and academics I know tend to set aside particular blocks of time for writing or require specific conditions in order to write, such as their own office, a blank desk or total silence. My schedule is pretty flexible in comparison. Part of this flexibility derives from working conditions I had during my Master’s and PhD degrees at Cambridge, where I usually wrote and researched in cramped spaces, such as the corner of an overfull table in the library, or the desk in the tiny bedsits in which I lived. Also, every day had a different schedule, in terms of teaching and other duties, so I trained my brain to work during whatever blocks of time were free. This training seems to have helped my poetry writing practice. "I usually wrote and researched in cramped spaces, such as the corner of an overfull table in the library, or the desk in the tiny bedsits in which I lived... This training seems to have helped my poetry writing practice."

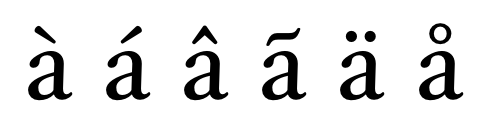

In your doctoral thesis, Thinking Outside the Hall, you investigate (among many other things) the evolution of the relationship between the skald (Norse poet) and their audience over different periods of time. Who do you envision to be your audience when you are writing poetry and in what way do you hope to engage them? Such an interesting question, Joshua, to think about how an imagined or expected audience might shape our works in conscious or unconscious ways! Skalds (and past poets from many cultures) often invoked specific audiences, who changed over the centuries in response to the evolving role of poetry in society. At the same time, the skalds also invoked future audiences and expected their poetry to be re-performed in unknown circumstances. Today I think this “dissemination mentality” is a more prominent influence on our conception of an audience. Poets often remain distanced from their audiences until they engage them on social media or give a reading. "Today I think this 'dissemination mentality' is a more prominent influence on our conception of an audience. The internet makes the question of how far our words will travel unanswerable. Does this broadness make it easier or more difficult to write? If we try to engage a specific audience, will it seem artificial and will we then lose sympathy with other audiences? Sometimes I mull over these questions. I try not to imagine any specific audience for my poetry or poetic translations, however, I do expect that an audience of my poetry would be willing to “work” a bit with the verse, partly because I enjoy poetry I can really sink my teeth into -- poetry which doesn’t immediately offer up all its treasures and secrets. That said, I would hope that any reader could derive some pleasure from one of my poems: if they are uninterested in the argument or subject matter, then hopefully they will find pleasure in the sounds and rhythms. "The internet makes the question of how far our words will travel unanswerable. As a scholar of Old Norse poetry you’ve spent a lot of time studying poetry in a language other than English. Does your time spent studying these ancient verses influence the English poetry you write today in any specific way? Absolutely. The subjects that Old Norse or Old English poets composed about don’t tend to inspire the subject matters I write poetry about, however, my academic training has had a huge impact on my verse. I’ll give two examples. Firstly, being attuned to sounds and rhythms considered gratifying in other languages has broadened my perspective on what kinds of sound and rhythm combinations are possible and pleasurable in modern English. I strive for unique and striking aural effects in my verse. Recently, I was pleased to discover a review of my chapbook, Biometrical, by Jeremy Luke Hill (on The Puritan’s Town Crier website), where Hill commented extensively on the kinds of aural play I use. For medieval Scandinavian skalds, sound was considered a structural “prop” holding up a poem, and among the most crucial factors determining form. Contrastively, many modern poets do not consider sound to be part of a poem’s form. Recently I heard a poet claim that they rarely use form in their work, but that same poet employs regular rhymes and chiming sound patterns in many poems! Perhaps modern poets could rethink how sound creates structure or form outside of a familiar rhyme scheme such as “abcb”. "...being attuned to sounds and rhythms considered gratifying in other languages has broadened my perspective on what kinds of sound and rhythm combinations are possible and pleasurable in modern English." Secondly, the ancillary disciplines I needed to study for my graduate work (linguistics, philosophy, history, art history, palaeography, etc), have given me a large store of ideas to draw upon, and I tend to weave concepts I find interesting from these disciplines into my work. When I’m looking for inspiration, I often find it helpful to be turned outwards as opposed to inwards, and (hopefully) avoid the pitfall of writing only about “me” experiences. Your poem Diacritics speaks of the loss of diacritical marks (e.g. ‘o’ vs. ‘ø’ in Norwegian) because of the pervasiveness of technology, specifically the typing of text on keyboards and our preference for web-based conversation. Do you think technology is causing language to suffer or do you think it is simply the next step in the evolution of human communication? Perhaps some of both. Diacritics was a poem I wrote in part about how “small things make big shifts” in terms of comprehensibility and meaning, between people of different cultures or backgrounds. The diacritical mark, as a small sign that makes a character function in a dramatically different way, became a metaphor for these differences we encounter in an increasingly globalized and digitized world. Technology gives us the opportunity to explore other languages, to hear them and see their characters, in ways not possible before. To me this is extremely exciting and I feel it should inspire people to use more words and learn new languages! In some ways technology has allowed this, in that many people use language apps or online translators, and thereby gain access to other languages. But a downside of technology is that it can make us lazy in our language usage. Some of the “voices” in Diacritics speak to this concern, as they push for addressees to switch to their own language patterns. "Technology gives us the opportunity to explore other languages, One of my favorite aspects of Norse verse is the use of kennings. (For readers unfamiliar with the term a kenning is a metaphorical phrase in Old Norse and English literature. For example, the ‘whale-road’ is a kenning for ‘the ocean’). As a scholar of Old Norse poetry do you have a few favorites you would be willing to share? Here are a few light-hearted and more unusual kennings from skaldic poems: -Jaw-lightning, for insults -Roof-shingle of the salmon’s hall, for ice -Forest of the brain’s farmstead, for hair -Bilge-water of the war-god’s wine, for bad poetry -Dirty-faced deceiver of the wood-bear of old walls, for a cat (the “wood-bear of walls” is a kenning for a mouse) The publishing environment for poets can be particularly difficult to navigate, but you have succeeded in publishing your own collection of poetry. Do you have any advice for emerging poets who are interested in getting their work published? Join a workshop group with poets whose work you admire and then hone your poems before submitting them to reviews. Send out lots of submissions and brace yourself for lots of rejections. Remember any encouragement you receive from a publisher or journal…it means someone will accept your work soon! Try to avoid writing about subjects you see everyone else writing about because you think it will help you get published (as a poetry editor at Pulp Literature, I can tell you these poems don’t usually stand out unless they approach a well-worn subject from a very refreshing or surprising angle). Attend readings and engage with the work of other poets, and read widely the work of exceptional poets. "Join a workshop group with poets whose work you admire and then hone your poems before submitting them to reviews... Attend readings and engage with the work of other poets, and read widely the work of exceptional poets."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJoshua Gillingham is an author, editor, and game designer from Vancouver Island, Canada. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed