|

Welcome Andrew! Thanks for taking some time to chat about writing. First, a few quick-fire questions: Who is the greatest Viking of them all? Which is the scariest monster you’ve ever read about? And what is your writing/translating beverage of choice? Technically not a Viking, (Vikings are Norse pirates) but I’m going with Leifr Eiriksson. Probably the most famous Norseman of them all, he actually was a peaceful man, the first European to set foot in the Americas (491 years before Columbus,) bringing Christianity to Greenland, and rescuing shipwreck victims. Scariest monster goes to Ungoliant from J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium. The Queen of the Spiders even scared Morgoth, Middle-Earth’s equivalent of Satan (who makes Sauron look like a schoolyard bully)! I also have arachnophobia, and Shelob is hard enough to watch in Return of the King, and Ungoliant is Shelob turned up to ten-thousand! I drink both tea and coffee, but I’m going to go with tea. Especially a P.G. Tips builder’s brew! "Scariest monster goes to Ungoliant from J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium." We both share a love and passion for Viking history, particularly the epics such as Beowulf. What drew you to study these texts and, in particular, to explore them through your own translations? I first got interested in history at age four because of Indiana Jones. I wanted to be an archeologist, so borrowed all kinds of books on ancient cultures, especially on ancient Egypt. A few years later, my focus shifted to medieval history. Later, I found out that Tolkien specifically based his works on Anglo-Saxon and Norse cultures, so my studies soon began to focus on the early Middle Ages. When I was 9, I was diagnosed with Friedrich’s Ataxia, a rare genetic disorder, similar to Muscular Dystrophy, and my pursuits became more and more academic, and less archeological. "Later, I found out that Tolkien specifically based his works on Anglo-Saxon and Norse cultures, so my studies soon began to focus on the early Middle Ages." Several years ago, I took a course on Old English from Michael Drout at Signum University (you can take the class as an Anytime Audit). At the end of the course, Professor Drout suggested we read Beowulf in Old English to become better acquainted with the language. Rather than simply read it, I decided to translate it into modern English and write an extensive commentary. Congratulations are in order for the publication of your new translation of Beowulf! Talk us through the journey of exploring this famous text and rendering it in this new translation. What are you hoping that readers take away from reading this story in this fresh light? For the original text I used a book called Klaeber’s Beowulf. When coming across words I was unfamiliar with I would use the Bosworth-Toller Old English Dictionary. Sometimes I chose to go with more archaic terms because it fit the alliteration better. I used more recent scholarship and that was reflected in the way I translated some of the words or phrases, for example: a damaged word in Line 587 is typically read as “hell,” but I offer the reading “hall” which gives the line a very different context. I hope that this new translation, with its alliteration, will harken back to older translations, such as those by Francis Gummere and John Clark Hall, but will also give it the accessibility of modern translations. "I hope that this new translation, with its alliteration, will harken back to older translations, such as those by Francis Gummere and John Clark Hall, but will also give it the accessibility of modern translations." Beowulf is getting a lot of attention right now with Maria Headley’s new translation, a very modern take on the tale, which was released a short while back. What are your thoughts on modernizing ancient texts like Beowulf and why is it important that these stories continue to be told today? While I don’t mind modernization of ancient texts, I actually had a much different intention for my translation. I feel that many recent translations modernize it so much, that it loses much of its beauty. I understand that pre-modern texts can be difficult to read, (that is the main reason I provided an extensive commentary along with the translation) but often they lose their alliteration and meter, which is much of poetry’s appeal. In talking with Dr. Alison Killilea and Norse epics student Rosemary , I complained about the lack of quality film adaptations of this incredible tale. Do you have a favorite film adaptation of Beowulf or do you have any ideas as to why it has been so hard to capture on the silver screen? My favorite movie adaption of Beowulf has to be The Thirteenth Warrior. Based on Michael Crichton’s novel Eaters of the Dead, it’s not a straightforward Beowulf adaption. It follows an Arab, Ahmad ibn Fadlan (portrayed by Antonio Banderas,) who gets caught up in an adventure with a band of Vikings, led by a warrior called Buliwyf (portrayed by Vladimir Kulich.) If you are familiar with Viking history, you may recognize the name ibn Fadlan; he was an ambassador from Baghdad, who gave an eyewitness account of a Viking ship cremation on the River Volga. Crichton wanted to show a possible historical basis for Beowulf, so he was trying to give a more natural rather than supernatural explanation for the monsters in the story. There are some anachronisms (such as Buliwyf wearing plate armor in one scene) and other inaccuracies, but the movie is well written. While not a perfect adaptation, it is probably the most entertaining adaptation I’ve seen. "My favorite movie adaption of Beowulf has to be The Thirteenth Warrior." As an author of fiction set in a Viking-like world, I often find myself challenging tropes associated with Vikings in popular culture. What false assumptions about Vikings or Germanic culture do you hope to address through your work with these ancient texts? A lot of popular culture portrays Vikings or Germanic people as people who would only raid and plunder, but I hope that with my different works people will appreciate that Vikings had their own culture and that they even had deep thoughts. When you take the time to study their culture and way of life, barbarian is no longer an adequate way to describe them. Can you give us a sneak peek of what your next major project will be? Any hints or perhaps a little snippet to get readers excited? My next big project is a trilogy of historical fantasy novels called Guthbrand’s Saga. I am hoping to have these novels traditionally published, so if you’re an agent or know of someone who is, feel free to contact me! The first book is completed and I am currently working on the second book. "My next big project is a trilogy of historical fantasy novels called Guthbrand’s Saga." The books are set in early 6th Century Norway, and are prequels to Beowulf. Book 1 is called Troll Bane. The story opens with Trolls raiding farmsteads bordering the wilds of Jötunheim. A jarl named Guthbrand and his small warband set out to hunt them down, but the closer they draw to a battle Guthbrand knows they can't win, his men's lives weigh heavy on him. Guthbrand’s Saga has characters and creatures from Norse mythology and legendary sagas. Characters share songs and folktales inspired by Old Norse sources. I paid special attention to surrounding this fantasy-infused story with historically accurate details and placing it in precise geographical locations so that you can even follow the party’s journey on a modern day map. I actually provide a map with the Old Norse place names. Like so many fantasy authors, I have been greatly inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Like him, I have tried to create an expansive world inhabited by people and creatures with their own rich cultures, languages and history. "I paid special attention to surrounding this fantasy-infused story with historically accurate details and placing it in precise geographical locations so that you can even follow the party’s journey on a modern day map. I actually provide a map with the Old Norse place names."

0 Comments

Much of your academic work centers around the Anglo-Saxon legend Beowulf. What was your first encounter with this text and how did it capture your imagination as a focus of your academic career? My first encounter was in first year of undergraduate with Dr Juliet Mullins in UCC. It didn’t capture my attention too much in the beginning, but as an 18 year old who was just becoming familiar with feminism, the lectures on Grendel’s mother and the other women of the poem really caught me! For my MA I held on to this fascination with Grendel’s mother and after seeing the Robert Zemeckis film from 2007 where her character is played by a hyper-sexualized gold-covered Angelina Jolie my interest peaked and I have been hooked ever since. "...as an 18 year old who was just becoming familiar with feminism, the lectures on Grendel’s mother and the other women of the poem really caught me!" I also may add that there is a movement within medieval studies to try not to use the term “Anglo-Saxon” due to its co-opting by racists - for instance before I studied the early medieval I thought Anglo-Saxon referred to WASPs! Due to the hard work by scholars like Mary Ramabaran-Olm and Adam Miyashiro among many others, the racisms within (and without) the field are really being highlighted. Your work with the legend Beowulf involves both translation and critical analysis of fiction inspired by it. I myself and a writer who strives to ‘reclaim and reframe’ the Norse Myths which have been very problematically debased over the past century in particular. What is the framework or approach you take to analyzing adaptations of Beowulf? What are some common problems and ways, perhaps for those who are working on their own adaptations, to avoid major pitfalls? I generally approach translations and adaptations of Beowulf through a theoretical framework, usually feminist or post-colonial, but also through a psychoanalytical framework too, whether that be Freudian, Lacanian, or Kristevan. My approach is often influenced by the cultural context from which the work comes, so for those awful 90s and 2000s films that came out around the time of third wave feminism (and are often backlashes against it), a feminist lens is often the best approach. For Heaney’s translation, which was written by a Northern Irish man shaped by the conflict in the North, a post-colonial approach is really fruitful. I am a firm believer in thinking that all translations and adaptations have something to offer, and I do try to be as unbiased as possible, taking a post-structuralist, Derridian approach to the idea of textual hierarchy - these texts should be judged in their own right, rather than in a comparative fashion. I think major pitfalls are generally just pitfalls that any novel or creative text would fall into. Perhaps with adaptations there is the temptation to fall back onto the poem and let the original carry the work, and I generally feel that those that try to be a bit more experimental (like John Gardner’s Grendel, Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead, and film-wise Howard McCain’s Outlander) are more enjoyable. "I am a firm believer in thinking that all translations and adaptations have something to offer, and I do try to be as unbiased as possible, taking a post-structuralist, Derridian approach to the idea of textual hierarchy - these texts should be judged in their own right, rather than in a comparative fashion." I’ve got to ask this as I’ve just finished reading Maria Headley’s brand new translation of Beowulf. What was your impression? What do you think it adds to the current selection of English translations on bookshelves today? And were there any translation decisions for which you would have taken a different direction? I am currently in the process of reading this translation myself, so I cannot make the most rounded opinion as of yet! Saying that, I so far have a mixed to positive response - I love the poetic language Headley uses, I find it so rich and beautiful to read. However, I am on the fence with the slang terms, as, while they make it a very contemporary translation, I can’t help but feel that some may become a bit passé a bit quick (e.g. “hashtag: blessed”). Of course, any translation that is a bit experimental and a bit different is a welcome translation in terms of its value as a rereading, and as a woman, it is great to see such a popular translation by Headley. It is in translations’ differences that make them the most interesting, and Headley’s, while I wouldn’t use it as a primary translation in terms of teaching, I would definitely use it as a means to showcase the reception of Beowulf and as a comparative work amongst a selection of translations. I also feel that it is a great text to make the poem more accessible and fresh and it will hopefully encourage a greater interest in Old English and other medieval texts! "It is in translations’ differences that make them the most interesting..." Another theme I notice both in your work and on your social media is reflections on the continuing development, however glacially slow, of a public conversation on the crisis of violence against women. What issues does Beowulf as a text raise for you on this topic and how do you feel like the academic discourse around Beowulf might contribute to the public discourse? I think Beowulf really exposes a society where there was a fear of female strength - we see this in the figure of Modthryth, whose power is used and abused and viewed with some amount of fear. Of course, more obviously we see it with Grendel’s mother, and I think Renee Trilling’s article “Beyond Abjection: The Problem with Grendel’s Mother Again” is a great theoretical analysis of the poem’s and the characters within it’s treatment of her character. She is numerous times referred to with male pronouns as if in this way Beowulf’s masculinity cannot be questioned (although this can also open up an insightful conversation about gender binary!), it is said she is less threatening than a man (even though she proves more stealthy and cunning), and only her son’s head is brought back as proof from the mere - almost as if she never existed. "I think Beowulf really exposes a society where there was a fear of female strength - we see this in the figure of Modthryth, whose power is used and abused and viewed with some amount of fear." It seems that a woman who dares to threaten the patriarchal foundation of Heorot is deserving of death. And unfortunately, this echoes in today’s world, where women are still murdered and assaulted for “daring” to wear what they want, to walk streets at night, and often in attempts to escape their abusers. In a lot of my work, I criticise the patriarchal actions in the poem, and indeed, along with other scholars view the 19th century idea of Beowulf as hero with a bit more scrutiny. It is a complex poem and should be treated as such, and I think the academic examination of the poem helps to expel the simplified discourse of “Beowulf is hero, powerful woman is monstrous”. I’ve been pretty serious here and would like to lighten things up with this next question, so here it goes: If you were given funding to direct a film adaptation of Beowulf then who would you cast in the key roles and where would you shoot the film? The million (or multi-million I guess) dollar question! This is something I have of course thought about every now and then over the course of the last ten years, and I actually do have an extremely rough outline of a novel adaptation - I’m just too busy (or lazy? scared?) to write it. This idea revolves around a 1980s or 1990s re-imagining set in a small rural Irish town somewhere in west Cork where the locals are being slowly murdered and some gardaí from the city have to come out and investigate. Maybe someday I will get to this! "This is something I have of course thought about every now and then over the course of the last ten years, and I actually do have an extremely rough outline of a novel adaptation - I’m just too busy (or lazy? scared?) to write it." In terms of films though, I have always thought that a more experimental and atmospheric rather than generic fantasy approach would work great. Think Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth (2015) crossed with the unnerving overtone of Robert Eggers’s films, The Witch and The Lighthouse. Lots of long slow shots with loads of atmosphere - maybe the Faroe Islands would be a good spot to shoot it! As for casting, I think the most important thing for me would be to have Grendel’s mother as a human figure. Films tend to cast her as either a monstrous hag (Beowulf and Grendel) or a hyper-sexualised sucubus (Graham Baker’s and Robert Zemeckis’s Beowulfs). What I think of when I think of her character is something along the lines of Virgil Burnett’s illustration, which appears in Kevin Crossley Holland’s translation. I think this would make for a pretty cool character and a nice change from the monstrous versions, or the sexy versions. And I often think about Charlize Theron in Monster where she plays serial killer Aileen Wuornos. Bernard Hill who played Theodon in Peter Jackson’s LOTR would be a great fit for Hrothgar, to capture the desperation we feel in his character. For Beowulf - that’s a tough one - but I think someone along the lines of Russell Crowe or Idris Elba may be a good fit. Can you give us a sneak peek of what your next major project will be, either a paper or a full-length publication? Any hints or perhaps a little snippet to get readers excited? Any day (week, month?) now I should have a chapter published in a collection called Transmissions and Translations in Medieval Literary and Material Culture, edited by Megn Henvey, Amanda Doviak, and Jane Hawkes. My specific chapter is about Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf and his revisionist approach to the poem, specifically concerning Grendel and Grendel’s mother, and how he transforms these characters into allegorical figures concerning the fight for Irish independence; Grendel as the soldier fighting for freedom from Britain, and Grendel’s mother as a Kathleen Ní Houlihan or Erin type character, an anthropomorphic Ireland, as it were. "My specific chapter is about Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf and his revisionist approach to the poem, specifically concerning Grendel and Grendel’s mother, and how he transforms these characters into allegorical figures concerning the fight for Irish independence..." Also, in the less serious and much much slower category of things, I have been working on my own translation of Beowulf into the Corkonian dialect! It’s a fun project that I update very semi-regularly! Last, but not least, where can readers find your work and keep up to date on your latest publications? Seriously, you need to treat yourself to some of Alison's Corkonian Beowulf translation on her website Boyo-wulf. Dowtcha boy!

Welcome Rosemary! Thanks for taking some time to chat about writing. First, a few quick-fire questions: What is your favorite kind of beverage to drink while writing/researching? Where is the best place to grab a coffee or tea or beer in Cork? And if you were put in charge of casting for an upcoming Beowulf movie then which actor would you recruit to play Beowulf? Thank you for the opportunity! I’ve been making iced coffees at home lately since the weather has finally picked up, so right now it’s those! Cork is blessed with so many lovely cafés. I tend to go to Vanilla and Co. on Cook Street, or Dukes Coffee Company on Carey’s Lane. For a Beowulf movie I would probably have to choose Henry Cavill. He’s fantastic in The Witcher so I’m sure he could do the poem more justice than what’s been offered so far. "For a Beowulf movie I would probably have to choose Henry Cavill. He’s fantastic in The Witcher so I’m sure he could do the poem more justice than what’s been offered so far." I’ve enjoyed hearing about your work on Beowulf through Twitter as well as on your blog, Fafnir’s Treasure Trove. I’ve found many academics are perhaps hesitant to engage the public on social media or through more personal platforms like blogs. What prompted you to start the blog and engage a wider audience? My blog actually began as part of my continuous assessment during my MA, so Dr Maureen O’Connor in UCC School of English and Digital Humanities has to get credit for it! I fell down a rabbit hole using it because it’s a space for testing out potential topics before diving into a conference paper. I think there’s this fear of your great idea being “stolen”, which I can understand but it can certainly happen in more traditional spaces as well, if someone stumbles across a note you publish, an article that they turn into a chapter or book, a conference paper they listen to, etc. You always run that risk. Social media has become more necessary for networking, especially since it isn’t safe to hold physical events right now. I think it is definitely going to continue to hold a place in academia whether we like it or not! Congratulations on completing your MA! Such a pursuit is a huge undertaking which I feel often goes unrecognized, especially by those who have not run the gauntlet of a graduate program. What advice would you have for writers who are considering taking a history-related MA? What are some potential upsides or downsides, especially as it relates to authors? Thank you! I think writers considering it need to take into account how much time is actually consumed by an MA. I only had around six hours of class time a week, sure, but the amount of preparation you need to put in before those classes is insane. Worth it but definitely mad. I find it difficult to only put in a half-hearted effort into anything I do so the MA quickly became my entire existence. I did a lot of extracurriculars during my bachelors and I had to pick and choose what I could keep doing and what I had to give up, because it was going to be impossible or quite unhealthy to continue trying to balance. "I only had around six hours of class time a week, sure, but the amount of preparation you need to put in before those classes is insane. Worth it but definitely mad." So be prepared to not have as much time to dedicate to other aspects of your life. Also be prepared for at least some people to not quite understand why you chose this discipline. I have no regrets whatsoever and the medieval continues to be the main feature for my life right now. But I definitely got a few interesting comments from others who just didn’t understand how it is relevant. I’m sure it sounds like a foreign language to my friends who have to listen to me babble on! One of your great passions/obsessions is the epic poem Beowulf! I was first ensnared by this spectacular piece of literature through Seamus Heaney’s translation. So I’d love to ask this: Why study Beowulf in 2021? What meaning or purpose does it have to our society hundreds of years later? Obsession is a good word to use! When I was in first year we actually used Heaney’s translation as well. As a proud Irish woman, it’s a great way to lure us in to the magic that is Old English literature. What we’re seeing right now is this wide reassessment of our relationship to gender and what our identity as a collective group of people or as individuals actually is. Part of the counter argument given to us is that “well back in the old days men were this, that, and the other, not this sort of tripe you’re banging on about!” "When I was in first year we actually used Heaney’s translation as well. As a proud Irish woman, it’s a great way to lure us in to the magic that is Old English literature." Take masculinity for example. You have many who argue that Beowulf is a perfect example of the traditional masculinity they feel is threatened by the social progress we’ve made in recent years. But looking at the poem, the image we’re given is actually so much more complicated but scholarship is only slowly starting to acknowledge that now. We’re also seeing a huge resurgence of the medieval in pop culture the last decade or so. But that leads to people falling down a rabbit hole and if we aren’t providing more nuanced arguments showing that gender and the medieval world are more complicated, where are they going to end up? More dangerous, extremist platforms for example. So it is definitely quite relevant considering both pop culture and the political scene in many countries right now! We also have to remember that a lot of narrative tropes that are still used in literature, film, etc. as well as the English language itself were shaped in these periods. Neil Gaiman, author of such best-sellers as American Gods and The Ocean at the End of the Lane, famously said that reads Heaney’s translation of Beowulf whenever ‘his blood needs stirring’. What are a few of your favorite translations and what unique features draw you to each? My go to for work is R. D. Fulk’s because he translated the entire manuscript and provides the Old English texts as well, so you can really dive into the original language, which is something that I think is quite necessary for the sort of work I’m doing! The use of Tolkien’s is quite dedicated to the structure of the Old English language so I like that one for those reasons. I also quite like Maria Dahvana Headley’s, which was only published last year! She uses terms like “bro” quite often, which is a great way of showing the comitatus society under a new light, especially younger audiences that might be used to modern “lad” culture as we call it here! The poem is undeniably a very male-centered poem after all! I am of the opinion that every film adaptation of Beowulf, at least the half-dozen that I’ve seen, are worse than bad… terrible actually. Do you think there is a decent movie adaptation of Beowulf out there? And what do you think makes the magic Beowulf hard to capture in the medium of film? I’d have to agree with you! There is an animated version for children that came out in the 90s but the narrative is heavily simplified. Accurate but simple. Though I imagine a 25 year old academic that is truly obsessed with the poem may not have been their target audience. The poem is so difficult to capture on film compared to maybe a later poem like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales due to the long speeches and dialogue. A lot of those side stories we get in the poem, like the mention of Heremod and Sigemund, or the past feuds the Danes and Geats were both involved in, give us a lot of substance for Beowulf’s character. They truly inform the reader about Beowulf himself. For example we have at the end of this story about how problematic Heremod was a king, and right at the end of that we have a link back to Beowulf himself, with the poet stating that “violence found a home in him”. So the poet inserts Beowulf into this story and that warns the reader of what is yet to come. But for a film that you watch, that complicates it too much. Audiences want at least some bit of action and not just two hours of speeches. So a clean timeline usually means removing those speeches but that then removes a lot of the substance that shapes main characters. "Audiences want at least some bit of action and not just two hours of speeches. So a clean timeline usually means removing those speeches but that then removes a lot of the substance that shapes main characters." So what do directors do to fix that? Change the narrative completely! So then it’s not even accurate! Filmmakers have to find a way around this. There’s violence in the poem of course but there is more to it. Those speeches are vital because Old English poetry was shaped by the oral traditions of their culture which were adopted into their writing! Removing that is removing a lot of what makes the poem so interesting. Can you give us a sneak peek of what you are working on right now? A few hints or an idea of what to expect in the next few months? I’ve definitely tweeted about this recently enough but I’m currently working on a paper for a conference this June. The conference is Death and the Afterlives of Medieval Mystics. I’m looking at the moral attitudes towards feminine bodies, pleasure, and sin in The Awntyrs off Arthure and the possibility that these attitudes were inherited from Old English hagiography. So I’m contrasting Gaynour’s Mother, the language used to describe her, etc. to some female saints from Ælfric’s Lives of Saints. I’m also studying Old Norse grammar as my supervisor wisely advised me that if I want to work more with Old Norse literature, it would be good to have the language. I covered Old English grammar last year during Ireland’s first lockdown! "I’m looking at the moral attitudes towards feminine bodies, pleasure, and sin in The Awntyrs off Arthure and the possibility that these attitudes were inherited from Old English hagiography." Last, but certainly not least, where can readers find more of your work and stay updated on your most recent publications? Other than my blog and my Twitter account, I usually end up posting papers on my Academia account as well. Twitter is probably the best place as I often tweet out my thoughts as they come into my head. You’re also guaranteed pictures of my cats. If you are in academic circles, be sure to follow Rosemary's Academia account!

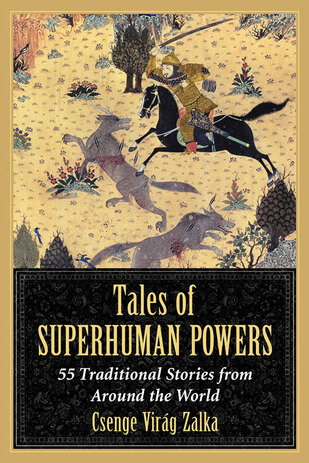

In the past few years you have published several books, been an active contributor in academic circles, and engaged a large audience through social media. Do you set a strict schedule to maintain this level of productivity or do you find other ways to sustain your work? I have a bullet journal. It is not very decorative, but it is great for making checklists, and I like checking things off (yeah, I’m an overachiever). I read a certain amount of stories each day with my breakfast, and most of my blogging and social media posts are scheduled for specific days. It also helps that I do a lot of the storytelling research purely for fun. Sometimes I just feel like looking up folktales about a topic, or from a place, and I enjoy going down the research rabbit hole. It’s one of the things I do for fun. "I have a bullet journal. It is not very decorative, but it is great for making checklists, and I like checking things off..." Your work on folktales from around the world spans both continents and centuries. Is this work driven primarily by personal passion or do you hope that your translations become contributions to the ever evolving conversation on globalization? It is mostly personal passion. I love learning about cultures through their stories. I started the “Following folktales around the world” reading challenge a few years ago, and I still have about 40 countries left to read folktale collections from! As for contributions: With my books I hope to bring Hungarian folktales to English-speaking audiences and storytellers, because they are not very well represented on the English language folktale market. On the flip side, I translate a lot of tales into Hungarian so that Hungarian audiences can have access to them as well. "With my books I hope to bring Hungarian folktales to English-speaking audiences and storytellers, One of your first books was Tales of Superhuman Powers: 55 Traditional Stories from Around the World. Today more than ever, North Americans are flocking to the theater to watch movies about superheroes and traditional story-telling media, such as comic books and graphic novels, are becoming popular again. Given your work in this field, what do you think draws people to stories about superheroes? Is it human nature? Is it a part of our mythos or culture? Is there perhaps something psychological at work?

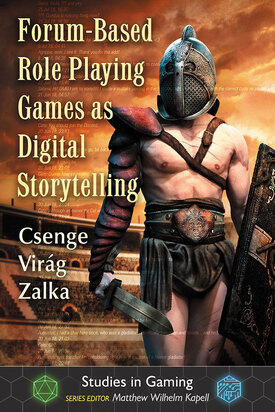

"My personal favorite thing about these “superhero” tales is teamwork. Earlier this year you released a book titled Forum-Based Role Playing Games as Digital Storytelling in which you describe an emergent form of digital storytelling facilitated through online platforms. Through this experience you discovered “a subculture of unbound creativity” as people wrote novel length descriptions of fictional characters and experience that they lived through these digital worlds. As a professional story-teller yourself, what drew you to engage with and study these emerging communities?

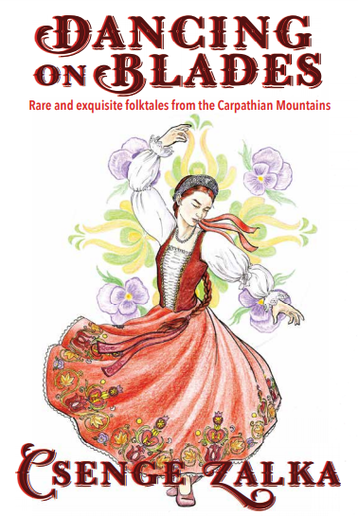

And the stories that come out of it stay online, and you can go back and read them for fun, or out of nostalgia. There are sites where I have been active for 8-10 years, and the stories still keep surprising and entertaining me. I love creating them in cooperation with others, rather than just writing things alone. In your 2018 publication Dancing on Blades: Rare and Exquisite Folktales from the Carpathian Mountains, you translate the tales of Anna Pályuk, a Rusyn woman who married into a Hungarian family. I find myself challenged by the task of ‘crossing cultures’ as I work with Icelandic source material from a different culture and time. How did you preserve the essence of Anna Pályuk’s stories while translating them for a modern reader? Were there any guidelines or strategies that helped to guide your process?

Joseph Campbell believed that common connections existed between stories from many parts of the world and summarized some of the key aspects of those similarities in what he called the Heroic Journey. Do folktales from around the world share much in your experience or have you found them to be highly distinctive to the culture they were first told in? I have a bone to pick with the Hero’s Journey. For one, it only fits a sub-category of folktales, usually known as wonder tales or fairy tales. The more one digs into different kinds of traditional stories, the less the theory holds up. Plus, as a storyteller, I tend to focus on how the story is embellished, rather than the basic plot. A lot of tales can be boiled down to “someone gets into trouble, then gets out of it”, but let’s be honest, that is not what makes one tale more compelling than another. There are tale types that exist all around the world, but I only ever really liked one or two variant of them and the rest just didn’t click, because of small details. "The more one digs into different kinds of traditional stories, the less the theory holds up. Where can readers find more of your work and stay up to date on your latest publications? I regularly blog through my website and I have a professional Facebook page. You can also follow me on Twitter.

|

AuthorJoshua Gillingham is an author, editor, and game designer from Vancouver Island, Canada. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed