|

Welcome Andrew! Thanks for taking some time to chat about writing. First, a few quick-fire questions: Who is the greatest Viking of them all? Which is the scariest monster you’ve ever read about? And what is your writing/translating beverage of choice? Technically not a Viking, (Vikings are Norse pirates) but I’m going with Leifr Eiriksson. Probably the most famous Norseman of them all, he actually was a peaceful man, the first European to set foot in the Americas (491 years before Columbus,) bringing Christianity to Greenland, and rescuing shipwreck victims. Scariest monster goes to Ungoliant from J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium. The Queen of the Spiders even scared Morgoth, Middle-Earth’s equivalent of Satan (who makes Sauron look like a schoolyard bully)! I also have arachnophobia, and Shelob is hard enough to watch in Return of the King, and Ungoliant is Shelob turned up to ten-thousand! I drink both tea and coffee, but I’m going to go with tea. Especially a P.G. Tips builder’s brew! "Scariest monster goes to Ungoliant from J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium." We both share a love and passion for Viking history, particularly the epics such as Beowulf. What drew you to study these texts and, in particular, to explore them through your own translations? I first got interested in history at age four because of Indiana Jones. I wanted to be an archeologist, so borrowed all kinds of books on ancient cultures, especially on ancient Egypt. A few years later, my focus shifted to medieval history. Later, I found out that Tolkien specifically based his works on Anglo-Saxon and Norse cultures, so my studies soon began to focus on the early Middle Ages. When I was 9, I was diagnosed with Friedrich’s Ataxia, a rare genetic disorder, similar to Muscular Dystrophy, and my pursuits became more and more academic, and less archeological. "Later, I found out that Tolkien specifically based his works on Anglo-Saxon and Norse cultures, so my studies soon began to focus on the early Middle Ages." Several years ago, I took a course on Old English from Michael Drout at Signum University (you can take the class as an Anytime Audit). At the end of the course, Professor Drout suggested we read Beowulf in Old English to become better acquainted with the language. Rather than simply read it, I decided to translate it into modern English and write an extensive commentary. Congratulations are in order for the publication of your new translation of Beowulf! Talk us through the journey of exploring this famous text and rendering it in this new translation. What are you hoping that readers take away from reading this story in this fresh light? For the original text I used a book called Klaeber’s Beowulf. When coming across words I was unfamiliar with I would use the Bosworth-Toller Old English Dictionary. Sometimes I chose to go with more archaic terms because it fit the alliteration better. I used more recent scholarship and that was reflected in the way I translated some of the words or phrases, for example: a damaged word in Line 587 is typically read as “hell,” but I offer the reading “hall” which gives the line a very different context. I hope that this new translation, with its alliteration, will harken back to older translations, such as those by Francis Gummere and John Clark Hall, but will also give it the accessibility of modern translations. "I hope that this new translation, with its alliteration, will harken back to older translations, such as those by Francis Gummere and John Clark Hall, but will also give it the accessibility of modern translations." Beowulf is getting a lot of attention right now with Maria Headley’s new translation, a very modern take on the tale, which was released a short while back. What are your thoughts on modernizing ancient texts like Beowulf and why is it important that these stories continue to be told today? While I don’t mind modernization of ancient texts, I actually had a much different intention for my translation. I feel that many recent translations modernize it so much, that it loses much of its beauty. I understand that pre-modern texts can be difficult to read, (that is the main reason I provided an extensive commentary along with the translation) but often they lose their alliteration and meter, which is much of poetry’s appeal. In talking with Dr. Alison Killilea and Norse epics student Rosemary , I complained about the lack of quality film adaptations of this incredible tale. Do you have a favorite film adaptation of Beowulf or do you have any ideas as to why it has been so hard to capture on the silver screen? My favorite movie adaption of Beowulf has to be The Thirteenth Warrior. Based on Michael Crichton’s novel Eaters of the Dead, it’s not a straightforward Beowulf adaption. It follows an Arab, Ahmad ibn Fadlan (portrayed by Antonio Banderas,) who gets caught up in an adventure with a band of Vikings, led by a warrior called Buliwyf (portrayed by Vladimir Kulich.) If you are familiar with Viking history, you may recognize the name ibn Fadlan; he was an ambassador from Baghdad, who gave an eyewitness account of a Viking ship cremation on the River Volga. Crichton wanted to show a possible historical basis for Beowulf, so he was trying to give a more natural rather than supernatural explanation for the monsters in the story. There are some anachronisms (such as Buliwyf wearing plate armor in one scene) and other inaccuracies, but the movie is well written. While not a perfect adaptation, it is probably the most entertaining adaptation I’ve seen. "My favorite movie adaption of Beowulf has to be The Thirteenth Warrior." As an author of fiction set in a Viking-like world, I often find myself challenging tropes associated with Vikings in popular culture. What false assumptions about Vikings or Germanic culture do you hope to address through your work with these ancient texts? A lot of popular culture portrays Vikings or Germanic people as people who would only raid and plunder, but I hope that with my different works people will appreciate that Vikings had their own culture and that they even had deep thoughts. When you take the time to study their culture and way of life, barbarian is no longer an adequate way to describe them. Can you give us a sneak peek of what your next major project will be? Any hints or perhaps a little snippet to get readers excited? My next big project is a trilogy of historical fantasy novels called Guthbrand’s Saga. I am hoping to have these novels traditionally published, so if you’re an agent or know of someone who is, feel free to contact me! The first book is completed and I am currently working on the second book. "My next big project is a trilogy of historical fantasy novels called Guthbrand’s Saga." The books are set in early 6th Century Norway, and are prequels to Beowulf. Book 1 is called Troll Bane. The story opens with Trolls raiding farmsteads bordering the wilds of Jötunheim. A jarl named Guthbrand and his small warband set out to hunt them down, but the closer they draw to a battle Guthbrand knows they can't win, his men's lives weigh heavy on him. Guthbrand’s Saga has characters and creatures from Norse mythology and legendary sagas. Characters share songs and folktales inspired by Old Norse sources. I paid special attention to surrounding this fantasy-infused story with historically accurate details and placing it in precise geographical locations so that you can even follow the party’s journey on a modern day map. I actually provide a map with the Old Norse place names. Like so many fantasy authors, I have been greatly inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Like him, I have tried to create an expansive world inhabited by people and creatures with their own rich cultures, languages and history. "I paid special attention to surrounding this fantasy-infused story with historically accurate details and placing it in precise geographical locations so that you can even follow the party’s journey on a modern day map. I actually provide a map with the Old Norse place names."

0 Comments

You are officially studying Egyptology at UBC but we bumped into each other during a fantasy reading event at White Dwarf Books in Vancouver. Of course, I do not find this surprising as most fantasy is inspired in part or in whole by history and mythology. As someone who studies these subjects formally, how does your academic background influence your experience of reading fantasy novels? Well, I do read novels that are set in an Egyptian context now, as I can understand the obscure the facts, even though they are very much exaggerating the culture. Authors like Wilbur Smith, and Elizabeth Peters (Elizabeth is actually an Egyptologist). But when it comes to classical fantasy books, I don’t think it has really changed anything. Other than not having a lot of time to read novels outside of studying. So I would say that I tend to read more YA or Adult fantasy that isn’t a huge epic, just because I don’t have the time or brain power to “study” another huge story. Authors like George, R.R. Martin, or Steven Erickson are way too “intense”. Authors like Jim Butcher, Brandson Sanderson, Dan Brown, etc…are ones I tend currently to gravitate towards. I love fast paced adventure. Of course there is Tolkien! He is my ultimate favourite! Well, I do read novels that are set in an Egyptian context now, as I can understand Your studies in Egyptology and ancient cultures have taken you to many incredible destinations including Turin, Italy and Cypress in the Eastern Mediterranean. What is the next travel destination on your research list and what do you hope to study there?

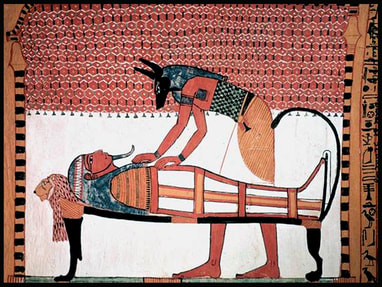

"I went to the Chicago museum which is attached to their Art Institute, and it was amazing. But I didn’t know what I was seeing, till after I started studying art history and then it made those pieces understandable in a whole new context." In your interview on The Tipsy Archives (a history podcast featuring just the right amount of wine) you mention that you have always been inexplicably drawn to Egyptian history and myth. I myself am drawn to the body of stories that make up the Norse myths and also have a hard time explaining what it is about them that I find so intriguing. Where do you think the power of myth is rooted and what about these stories makes them relevant today? Ooh, that is a tough question, as we talked about briefly in person and via email, I too am also drawn to Norse myth, I have just academically studied Egyptian myth more. I think the power of myth lies in its ability to captivate a reader/listener because it is relatable. In myth, a reader can find hidden cultural gems of information that would otherwise have not been discovered. There is only so much that archeological evidence can tell us, albeit quite extensive, but nevertheless myth and story hold a culture’s “essence” or values. It is important I feel, for us to share and remember these stories cause then these cultures that do not exist in the same fashion as they used too come back to life and are remembered. There is only so much that archeological evidence can tell us, albeit quite extensive, In your essay The Portable Shrine of Anubis, you mention how the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb gave archeologists unparalleled access to information about Egyptian death customs which other fields of archeological study surely view with envy. As we come from a modern North American culture that does not like to dwell on death (but rather obsesses over a glorified version of youth), what strikes you as profound in ancient Egyptian beliefs about death?

"Most seem to think that they are a culture that is obsessed with death, and that they worship it (hence all the pop culture-egyptianizing) but they were in fact quite scared of death, and as such had all of their rituals around death so that they could keep on living in the next area they called The Field of Reeds." Same like the grave goods, as you needed all of those items with you so that you could continue on. For the Egyptians, magic and death were literal. For example, if you drew a person missing an arm, then that person would have no arm in the next life. So you needed to make sure that once something was drawn, written, placed, that made it so. Death and life were interconnected to them. In your research paper Soundscaping in the Ancient World: Weaving through the Writings of Time you discuss the importance of sound, as well as silence, in Egyptian language and culture. As my field of study involves the language Old Norse, sound becomes paramount because it was an oral culture with no official written language. However, today so much communication happens visually instead of audibly. What do you think we lose when we move away from auditory language towards text-based communication?

"I think we lose the emotions. We lose empathy. We lose our ability to become personal with people." The ideological fanatics Nazi Germany in World War II seemed drawn to myths and sought to exploit them for their cultural power. Beyond the Germanic and Norse myths, Nazi archeologists tried, in a bizzare blending of fact and fiction, to prove that the Egyptian pharaohs were ancient Aryans. These bewildering notions still feature heavily in popular conspiracy theories. What do you think the role and responsibility of researchers and historians is in addressing such wildly inaccurate and potentially destructive ideas? Researchers, historians and archaeologists need to publish their work!!! This is a real problem! There are many people out there who are doing amazing studies but that information never gets told to the public, and therefore stupid theories arise and you get Egyptomania and the misinformed meanings of symbols, be they Egyptian or Nordic. "Researchers, historians and archaeologists need to publish their work!!! This is a real problem!" As our role is to study the past, we need to do that in a professional, respectful way and to realize that it doesn’t matter where people come from or what they believe in, we are all here on this planet and we are here to keep our heritage alive. It is about cultural heritage. Educating and involving the locals about their own culture so that they can learn about what was lost to them as well as to us. "It is about cultural heritage. Educating and involving the locals about their own culture Where can Egyptology fans find more of your work and stay up to date on your latest research? Ha! I will be uploading some of my essays, like the ones that you mentioned here, on my academia.edu page (once school is finished).

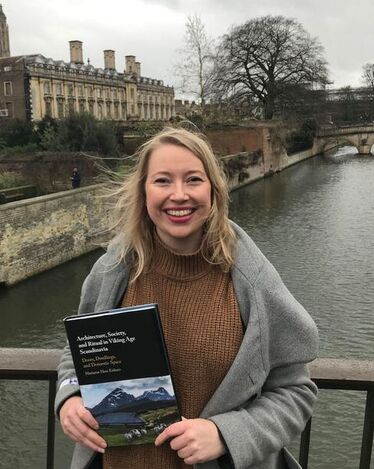

What does a productive day of writing look like for you? Do you write in your office at the university or do you prefer to write at home? Do you have a writing schedule or do you write around the rest of your professional commitments? I ponder my writing practice quite a lot. I have no rigid writing structure, but as many others, I often write best first thing (which is not necessarily very early, as I am a night owl). If I am on a deadline I wake up and immediately start writing in bed (don’t tell my physical therapist). But of course I do have to write around other commitments. I usually do better if I plan writing slots and add them to my calendar, and best if I also specify to myself in some detail what to do in such a slot (e.g. ‘write one paragraph on houses as social technology’). "If I am on a deadline I wake up and immediately start writing in bed (don’t tell my physical therapist). I have a daily writing target of 500 words — which is not excessive. I am quite a slow writer and a ‘poor first draft’ sort of writer, meaning that I have to plan for time to revise the text to make the arguments click and, hopefully, make the writing both clear and evocative. As a non-native speaker publishing mostly in a second language, there’s a separate set of challenges there — but English has been my academic language for such a long time now, that I struggle more to write academic text in Norwegian, to be honest.

A lot of people are really fascinated with the Vikings at the moment, but I think it is important to shed focus on the flip side of the traditional narratives of kings and warriors too — and talk about the lived experiences of the unfree populations, of being a low-status woman in societies with a strong ideology of violence, and uncomfortable topics such as infanticide. We are all fascinated with the past, but we shouldn’t glorify it. "We are all fascinated with the past, but we shouldn’t glorify it." As I talk to other writers whose work falls into the category of either historical fiction or non-fiction they often speak of the enormous amount of time they spend researching their areas of interest before sitting down to write. This is obviously a significant addition to the already laborious task of writing a book. Do you have any research tips for aspiring writers of historical fiction or non-fiction to help streamline their process? I’ve never published fiction, but for my writing practice I often research and write simultaneously. Again, this means having to revisit and rewrite text as my thinking on a certain topic develops, but to me the two processes are entwined — I write to clarify my thinking — and therefore it is too artificial to divide the process into two separate tasks. "I write to clarify my thinking — and therefore it is too artificial to divide the process into two separate tasks." In 2015 you took up the role of editor for the publication Viking Worlds: Things, Spaces and Movement, which illuminated a variety of perspectives on exploring Viking history. As a writer of Norse-inspired fiction I am always fascinated by the reverberating effects of Norse culture across the world throughout time. What were a few of the most interesting conversations around current and future research in Viking studies that Viking Worlds raised for you?

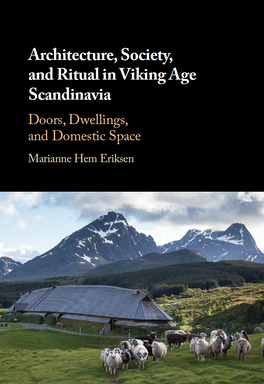

Your most recent book, Architecture, Society, and Ritual in Viking Age Scandinavia, explores Viking culture through the lense of architecture with a special focus on the meaning and symbolism of doors. My brother happens to be a practicing architect on the East Coast of Canada and can read far deeper into physical structures than I manage to. How did you approach this study of culture through structural forms and what applications might this have for writers? Someone once said that architecture is a totalitarian activity. By ordering space you are also controlling how people move, what they see, where they execute different activities, whether their bodies feel small and minuscule (as in vast cathedrals), or trapped and claustrophobic, how they view the world. Social space is social order. "Someone once said that architecture is a totalitarian activity. By ordering space you are also While several books and archaeological reports have considered the technical aspects of house building or the resource management of Viking settlements, I wanted to flesh them out as real people specifically through their use of architecture. Through a new compilation of houses in Norway, 750-1050 CE, I considered household size and structure, analysed movement patterns, the landscape placement of houses, their ideas of privacy, and the ritualisation of houses; which can be seen for instance in the practice of covering houses with burial mounds (accepted manuscript version here). "I wanted to flesh them out as real people specifically through their use of architecture." The implications of these approaches is to challenge some of our own assumptions of where meaningful social action takes place: it is not only on ships or on battlefields, and what happens in the domestic sphere is connected to, and also driving, larger socio-political structures. Architecture, Society, and Ritual in Viking Age Scandinavia challenges the often male-focussed lense of Viking history research. How has Viking architecture contributed to our knowledge of the influential role of women in Viking society and what specifically do you think might surprise readers?

I also consider, based on others’ research as well as my own, whether placed deposits of particular artefacts in houses (so-called ‘house offerings’), may be a ritual practice linked with women — which may help explain why it is not recorded in the medieval written sources (which, obviously, were all penned my elite males). What can readers look forward to next from you and where can they keep track of your latest publications and appearances? I have some things in the pipeline: a book chapter will be coming out in 2020 about whether people in the Viking Age dreamed of houses (spoiler alert: they did); another entailing a new consideration of Bronze Age houses and households; and I am currently seeking funding for a larger project on the deposition of human remains in settlements in the first millennium CE, a topic on which I also have a journal article under review. Further down the line there are a couple of books under development. I always have (too) many writing projects going.

People are welcome to keep track of my work on my website or follow me on Twitter. (I must admit, I am still really bad at Twitter, but I try — perhaps a New Years’ resolution is in order?) |

AuthorJoshua Gillingham is an author, editor, and game designer from Vancouver Island, Canada. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed