|

This past year has been turbulent to say the least; with the number of ups and downs, I still can hardly tell whether I’m standing on my head or on my feet. However, one of the most notable ‘ups’ was that I ran a successful Kickstarter. Then I ran another one. And then one more! In fact, in the past ten months I ran three successful Kickstarter campaigns and collectively raised over $35 000 USD for an Old Norse phrasebook, a Viking-themed card game, and an anthology of historical fiction. This does not make me a Kickstarter expert by any stretch of the imagination, but I have learned a few things and I hope to pass on a bit of insider knowledge here for crowd-funding hopefuls considering this route to publication. "[In] the past ten months I ran three successful Kickstarter campaigns I have an idea. Should I run a Kickstarter? If any creator was to ask me this question, I would ask them three questions in return:

If you answered yes to these three questions then I think your idea is probably viable for a Kickstarter campaign. (Note: ‘viable’ does not guarantee success.) If you answered no to any one of these three questions I would strongly discourage you from pursuing funding through Kickstarter. Instead, I would suggest that you pitch your idea to publishers who can handle the items above while you focus solely on the creative aspect of the project. "If you answered yes to these three questions then I think your idea When should I start working on the Kickstarter? I think there is a misunderstanding of timelines when it comes to Kickstarters for new creators. Way back in the day, the idea of pitching a project, getting it fully funded, then working on it for six months to two years while backers wait patiently may have been an option. These days, you want to have a fully finished product (be that a game, book, album, etc.) as you will be competing with very polished products for attention and for funds. My suggestion would be to complete the ‘idea to reality’ stage first, make sure it really is as awesome as you were hoping it to be, and then begin to prepare for a Kickstarter campaign launch. " My suggestion would be to complete the ‘idea to reality’ stage first, make sure it really is as awesome as you were hoping it to be, and then begin to prepare for a Kickstarter campaign launch." I would budget about 5-15 hours a week for pre-campaign work (designing graphics, recording the video, networking, securing promotions, getting feature spots on podcasts or in relevant publications, developing publicity materials, recruiting followers on the pre-launch page, etc.) for about three months before the campaign and then 15-25 hours per week during the campaign. Any work you complete before the campaign will be very much appreciated by your future self during the mid-campaign madness. I highly suggest working with a partner (or a team) on this as that is a lot for one person to handle while remaining somewhat sane. What funding goal should I set for my Kickstarter? This is highly dependent on what the product is, but in general you obviously want to cover the cost of printing or production. Be sure to get a quote for this before you set your funding goal and do not just ballpark your costs. If you’ve never worked with a printer or a manufacturer before then do your homework early in the planning stages. I had friends who funded their board game on Kickstarter then received copies from the manufacturer overseas, 30% of which were defective. They were on the hook to cover thousands of dollars of re-printed games out of pocket; it was either that, or lose the significant following they had built upon Kickstarter over several successful projects. Additional expenses, which can be significant, include Kickstarter’s 5% fee, warehousing and distribution, and any costs related to fulfillment management services. Typically it is understood that backers will be charged shipping (be very careful if you plan on including shipping in the backer price) and most creators, even small ones, will use a fulfillment manager such as CrowdOx to help with post-campaign delivery. I would highly recommend that another buffer of at least 5% be added to the funding goal to cover any unforeseen expenses related to the campaign. "I would highly recommend that another buffer of at least 5% be added to the funding goal to cover any unforeseen expenses related to the campaign." Of course, there is also the whole issue of your being paid for the creative work you have done. I would suggest using the Kickstarter to fund the production costs or the print run then pay yourself through post-campaign sales. For example, if you fund a print run of 2000 copies of a book and you have 800 backers, then there are 1200 copies that can be sold post-campaign. Not everyone would agree with me on this, but consider the fact that you are paying Kickstarter 5% of your ‘creator’s fee’ if you raise those funds through the platform. I just launched my Kickstarter! Time to sit back and let the pledges roll in? (Spoiler Alert: The answer is no.) No amount of pre-campaign preparation can prepare you for the rush, the thrill, and the terror of your campaign launching on Kickstarter. You are baring your soul, your dreams, and your ambitions to a nebulous universe of interconnected intelligent entities surfing across the vast expanse of the web. When the campaign begins, it is time to start pushing harder than ever to reach new audiences, network with influential people around the topic of your project, and follow up with media features you set up during the pre-campaign. During my third campaign we were fortunate to be selected as a ‘Project We Love’ by Kickstarter. Our campaign was featured on the ‘Project We Love’ page and we were given access to a promotional badge which helped us stand out. Only 8-9% of all Kickstarter projects are selected to be in this category so it is a significant achievement; however, there is no process to apply for this status as projects are selected using a secret process that happens behind closed doors. "During my third campaign we were fortunate to be selected as a ‘Project We Love’ However, if you look at the current ‘Projects We Love’ page you can identify some themes in terms of which projects are getting selected. While not every project might fit into this category, consider tweaking your campaign page to try and catch the eye of a Kickstarter administrator. Note that your campaign might be live for several days before you receive notice that your project has been chosen as a ‘Project We Love’ and such a designation does not guarantee success. My Kickstarter is live and it is not doing very well. Should I pay for advertising? This is, unfortunately, an all too common experience, especially for first time creators. Overall, only 38% of projects on Kickstarter reach their funding goal by the end of the campaign. Creators need to be prepared for the worst-case scenario but should not sit back once the campaign begins. The energy of the campaign, especially in the first few days, will be key to either its success or its failure. It is very common to have a mid-campaign plateau and that is nothing to panic about. The spike of pledges in the first few days and the rush of backers who had been following the project or holding back in the final hours are like riding an extreme roller-coaster, but this middle section can feel like trudging through a desert of despair. At this stage, if the project has not yet funded many may feel immense pressure to pay for advertising in a desperate attempt to reach more people. "The spike of pledges in the first few days and the rush of backers who had been following the project or holding back in the final hours are like riding an extreme roller-coaster, but this middle section can feel like trudging through a desert of despair." I would caution against paid advertising in general. If you have a background in SEO analytics or marketing then maybe you can turn this to your advantage. However, paid advertising will never, in my opinion, be able to match personal recommendations. Having an influential podcaster, author, or academic personally share your project and encourage people to back it is more authentic than paid advertising and will attract the kind of loyalty that these projects need to succeed. People need to believe in the project like you do, and that sense of communal excitement is difficult to generate without personal recommendations. Besides, there are plenty of people ready to take your money with baseless promises of Kickstarter success, but once they are paid your money is gone, gone, gone. My Kickstarter is funded! Now what? Ah! You’ve reached that enviable state for which so many have striven. However, there is still much work to be done in finalizing the production of your campaign, fulfilling orders, and staying in touch with backers. One thing I was surprised to learn is that many of the pledges bounce, sometimes upwards of 10% of all pledges; Kickstarter has no way of securing these funds if the payment information is not current and backers do not update their details before the funds go through. This is not too much of an issue for campaigns that significantly overfund, but if you barely make it over the line at, say, 102% funded on a $9000 goal, you may end up with only 95% funding once all the funds come through. This is yet another good reason to build in a bit of buffer in your original funding goal. "One thing I was surprised to learn is that many of the pledges bounce, Last, but not least, if you begin creating projects through Kickstarter you are likely to continue with future campaigns that expand on your series, universe, or game. While answering mountains of backer questions, wrestling printers to meet your promised deadlines, and interacting on social media, remember that these amazing people who backed your project may be interested in backing future projects, provided you’ve shown yourself to be reliable and professional. Keep backers up to date and inform them of delays in fulfillment or any other items relevant to the campaign. "...remember that these amazing people who backed your project may be interested in backing future projects, provided you’ve shown yourself to be reliable and professional." All of this is really just scratching the surface of the wild and wonderful world of crowdfunding; if you are interested in learning more I encourage you to check out the extensive collection of posts by Stonemaier Games or to send me an email through my contact form for more specifics on any of the topics above. Keep making the world a little bit more awesome with everything you create! For more from Josh, explore the sub-category 'Articles' on this blog or following him on Twitter!

0 Comments

However, my wife will always choose something new. Always. I have to admit that I owe some culinary revelations to this habit of hers, including my addiction to sushi and a discovery of the treasure trove that is Lebanese cuisine. But to be honest, the majority of new dishes we order are disappointments that we have no desire to encounter again. Is it worth it for the rush of discovering a delicious new food? Sure. Is it enough to stop me from ordering a pulled-pork sandwich or a pad thai for the one-hundredth time? Definitely not. So what does all this have to do with writing genre fiction? Well, some might say that reading genre fiction is a bit like ordering pulled-pork sandwiches over and over, that it makes you predictable (i.e. boring). Others might add that writing genre fiction is little more than an act of trying to resuscitate long-dead tropes while trying to pass off cheap imitations as original work. Given these two stereotypical notions, especially within the writing community, there can be a lot of shame or defensiveness around reading or writing these kinds of stories. Therefore, I feel the need to present an argument in defense of genre fiction, its readers, and its writers. "Therefore, I feel the need to present an argument in defense of genre fiction, its readers, and its writers." I would love to include a comprehensive list of all that is included under the umbrella of ‘genre fiction’, but there are endless branches and sub-branches which spiral down toward infinity in fractal patterns. Some of the most popular are Romance, Westerns, Mystery, Horror, Thrillers, Fantasy, and Science Fiction. If you are a writer or reader of any genre, or aspire to be one, this rant is for you. (And if not, feel free to go read a dictionary…)

So I’ll just go ahead and say it straight: I write Fantasy. I write cursed swords and magical monsters and medieval feasts with calorie counts high enough to kill an olympic weightlifter. I don’t have a BA in History, in Poetry, or in Literary Criticism (though I’m sure those are all great degrees to have) and I don’t aspire to be published in a literary journal. My aim in writing is not to win an argument or to show off my intellectual prowess, and it is certainly not to win prestigious literary awards to line my shelf with. "I write Fantasy. I write cursed swords and magical monsters and medieval feasts

"My highest aspiration as a writer is this: to write the book that people keep on that extra-special place on their shelf, the book whose pages are wrinkled and stained from use..." I write Fantasy because I strive to create the kind of stories I want to read. I want adventure. I want magic. And most of all, I want worlds unbounded by the shackles of our present reality or belaboured past. That is the kind of story I crave when I feel numbed by the drivel of the day-to-day, when I feel crushed between the cogs of ‘the system’, or when the itch for adventure is so insistent I can no longer ignore it. Of course, that doesn’t mean I won’t reference history or challenge real political or philosophical ideas; what it means is that I have a safe place to explore and create, a cushion between raw reality and a mental other-space where it is easier to think, explore, and feel. "That is the kind of story I crave when I feel numbed by the drivel of the day-to-day, when I feel crushed between the cogs of ‘the system’, or when the itch for adventure is so insistent I can no longer ignore it." Despite my love of Fantasy, many writers of genre fiction get it wrong. Really wrong. Their plot lines get tangled in tropes, their characters end up skewered on tired stereotypes, and the overcooked hyperbole of their world causes it to collapse in on itself. In fact, these fumbled attempts at imitation, rather than creation, are what give genre fiction a bad name in the writing world. So where does good genre fiction start? Well, it starts with a promise.

"Promise is the foundation of genre fiction... You must fulfill the promise of your genre But don’t stop there. Give your genre fiction something extra. Zest it with a character or an idea that will catch your reader off-guard, that will make them think, that will stay forever impressed on their minds. Give them the rush and the escape that they have felt before while reading that genre and then dazzle them with something they never expected.

So don’t be ashamed of writing or reading genre fiction. If you are a writer then start with the promise and build off of that foundation. If you are a reader, don’t settle for dry characters or soggy plot lines. Now, you’ll have to excuse me because I am really craving a pulled-pork sandwich... For more advice about writing genre fiction, Joshua recommends listening to the Writing Excuses podcast.

Know that this article was inspired by recent and very real events. A few weeks ago I received an edited manuscript from a very patient editor, almost three-hundred pages absolutely covered in red-slashed edits. Flipping through it was like fast-forwarding through a B-grade slasher film. A few days later, I got a review back from a female beta-reader who said that the mother in the story wasn’t landing properly and that a risk I took near the end, a scene that was meant to be the narrative climax of the second book, bored her. Double ouch. So let’s get real about what the editing process is like and how to survive it. "...almost three-hundred pages absolutely covered in red-slashed edits.

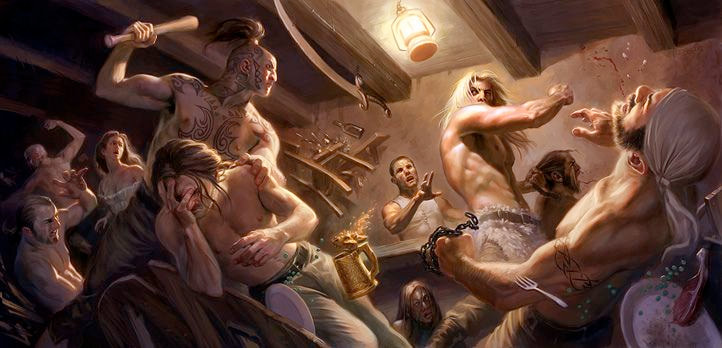

Principle 1: Force equals mass times acceleration.Application to Bar Fights: Big people (i.e. big mass) don’t have to move very fast (i.e. low acceleration) to throw forceful punches. Small people (i.e. small mass) need to strike extra fast (i.e. high acceleration) to hit with the same kind of force.

By the way, this rule also explains why sugar-coated feedback (i.e. low acceleration) is not helpful. It doesn’t matter if you are dealing with a big mass or a small mass; if it’s moving really slowly it isn’t going to hit with noticeable any force. "...get strangers or friends-of-friends (i.e. small mass) to review it in order to lessen the force when those criticisms hit." Principle 2: Force can also be viewed as change in momentum over time.Application to Bar Fights: Bones don’t break because they are moving really fast. Bones don’t break because they stop moving. Bones break because they go from moving really fast to a complete stop really quickly. It’s the difference between being shoved up against a wall and being thrown into it.

Principle 3: Intensity of impact is proportional to an object’s rigidity.

"This principle is also the reason you can go diving into a pool of water but not into a pit of gravel." Application to the Editing Process: The more nervous you are about others critiquing your work (i.e. rigidity) the harder their criticism is going to hit you. This is unfortunate because that means your own fear of criticism is proportional to how much it is going to hurt when it inevitably comes crashing into you. So don’t tense up. Pretend you are someone else looking at your work. Even better, treat the work as if it was someone else’s story or poem. The more you can relax into the idea that your story is going to take a few hits, the more efficiently you can spread the impact of that criticism around. "Pretend you are someone else looking at your work.

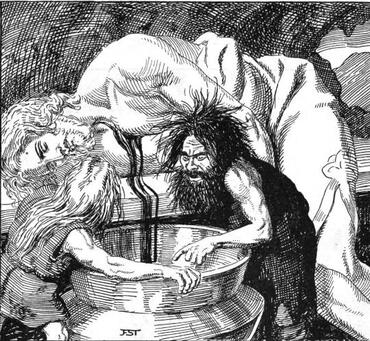

In light of these depictions, you may be surprised to learn the historical source material for dwarves in fantasy, the Norse myths, portray them as unequivocally evil. Though not even the Norse gods enjoy the benefit of the doubt with Odin himself being nicknamed Bolverk (Evil-Doer), dwarves were viewed as particularly vile. At one time they had supposedly been maggots wriggling in the dirt which were given the wits of men; with such repulsive origins they might be viewed as a symbol of the greed, lust, and violence that marked most of the Viking Age. (And if you think that is an ignoble birth then consider the fact that Ymir spawned giants out of congealed sweat in his armpits...) "At one time they had supposedly been maggots wriggling in the dirt which were given the wits of men..."

"The dwarven brothers tied him to the chair and cut his throat so they could catch his blood in a vat.

"Mighty Fenrir is brought low when the gods call on the dwarves to craft the strongest chain of all;

There she comes to the dank cave of four dwarven smiths who are admiring their latest creation, In my own writing I have worked to honor the original conception of the dwarves as presented in the Norse Myths while taking care to remain sensitive to the historical contexts in which the myths have been abused. Particularly heinous are the propaganda posters used to instill hatred toward people of Jewish descent during World War II; an honest evaluation of these political weapons will admit some clear lines being suggested between people of Jewish descent and the dwarves from Norse Mythology. Further, some adaptations of Wanger’s ring cycle clearly present Norse dwarves as pseudo-Jewish type characters which is yet another example of the toxic racism that led to one of the darkest chapters of human history.

Instead of abandoning the myths to those who would weaponize them for ill purposes,

Were they metaphors for human lust and greed? Were they archvillians to flesh out a world full of heroic gods? For more on the history of the Norse Myths and their modern interpretations, Joshua recommends

From Asgard to Valhalla: The Remarkable History of the Norse Myths by Dr Heather O'Donoghue. Stay up to date on Joshua's latest books by joining the Trollhunters! Start Marketing NowStart your marketing campaign the moment you type ‘The End’. In fact, you might be better off to start marketing your story even before it is finished. The essential first step is to establish yourself online with an author website if you have not already done so; I find that both Weebly and Wix are excellent options for building a basic site that looks professional. If you buy your own domain it may include an email, depending on what package you purchase. If not, it is important to get a professional email through which you can correspond with agents, publishers, and future readers. Start creating a mailing list early on as this will be your most essential marketing tool once the book comes off the printing press. Most authors I know use MailChimp which is slick and secure; it also happens to be free until you get over two hundred and fifty subscribers. While social media presence is looked upon favourably by agents and publishers, I suggest choosing one platform and focussing on it exclusively. Start creating a mailing list early on as this will be your most essential marketing tool Edit, Edit, Edit

I suggest searching through lists of editors provided by writers unions (The Federation of BC Writers has an extensive list of suggestions) or through freelance work sites like Upwork. While editors on social media may advertise significantly cheaper rates, considerations of accountability, quality assurance, and tracking payments leave freelance websites and vetted professionals as the prefered options. Get Beta-ReviewsNo matter how deeply your story resonates with you, it is not ready to send to agents or publishers until at least a few people have read it with a critical eye. This is difficult to achieve as reading a full length manuscript of 80-100 thousand words is no small task for most individuals. Your spouse or partner is likely invested in your success and so may provide very detailed feedback about things like spelling errors and story inconsistencies. ...your story [...] is not ready to send to agents or publishers until

Write a Stellar PitchWriting is, of course, about ideas and characters, about transformation and passion, about discovery and adventure; most of all it is about telling a truly great story. However, agents and publishers are not in the passion business. They are selling books. To customers. For money. It is very important to keep this in mind when you write your pitch. However, agents and publishers are not in the passion business. They are selling books. To customers. For money.

A few ‘Do Nots’:

A few ‘Dos’:

Set up a Query Schedule

Persistence is key at this stage. A long term investment of time and energy wins over short bursts of query flurries. In addition to consistency, target your queries and craft each one to suit the agent or publisher your are contacting. Two or three well-researched queries are better than ten generic emails which I can assure you will be duly ignored. I suggest starting with a bit of research on who represents or publishes your favorite authors or those who write in a similar genre similar. Recognize also that there are many (many, many, many) people trying to achieve the dream of publication. Therefore, each query you send must be unique and memorable if it is to be worth sending at all. Each query you send must be unique and memorable if it is to be worth sending at all. Start Writing the Sequel

Consider this: What if your book does get published? What if it is a success? What then? If all you’ve done for six months or a year is work on all the steps listed above then you may have sunk your own ship. Once readers hear of you they are waiting for the next book in the series, the next stage of the journey, or the next big idea from their new favorite author. You don’t have another year or two to write that story. Fans, while wonderfully supportive, are not known for being a patient crowd. You don’t have another year or two to write that story. You need another manuscript ready for your agent or publisher as soon as your first book starts to attract attention. At this point, you have put so much time and energy into getting the momentum of your writing career started that you must keep it going. And so the cycle continues. A Final WordIf all this seems overwhelming, I unfortunately must admit that it is. However, one small reassurance is that in writing your next book and the one to follow that, you have already established a fanbase, a mailing list, and an online presence. Getting reviews will get easier as you become known in a wider range of literary circles. Most sequels sell far better than the first book in the series (as long as the first book was well received). Last, but not least, know that while there are many barriers to overcome on the path to publication, no one can stop you from writing your story. So muster your courage and write it. No one can stop you from writing your story. So muster your courage and write it. Join Joshua's mailing list for articles on writing, featured author Q&As,

and updates on his Norse-themed fantasy series, The Saga of Torin Ten-Trees.

Fantasy brings to mind worlds of pure imagination. As an author this can feel like a nearly limitless power to craft any realm you desire and these worlds are so wonderful precisely because they are not our own. But that feature is also a limitation: the characters within the fantasy world should not (in most cases) have knowledge of our world. A critical issue arises when certain elements of our present reality leak into character dialogue or scene descriptions, an issue in fantasy which I call the problem of a leaky world. A critical issue arises when certain elements of our present reality leak into character dialogue or scene descriptions,

...it is easy to let certain things slip through the narrative that are references specific to our reality; the effect of such a mistake is to yank the reader out of the fantasy world momentarily and break the spell of imaginative literature. Consider the following cliche which might easily slip into a scene of dialogue between two characters. “Give them an inch and they'll take a mile!” The issue with this phrase in the context of a fantasy novel is neither the idea that is being communicated nor the fact that it is a cliche in English culture (as using cliches is just lazy in general); the ‘leak’ is in the specific reference to ‘inches’ and ‘miles’. To refer to ‘inches’ and ‘miles’ in a fantasy novel is to directly reference an important part of the real history and development of our culture. This suggests that either these fantasy characters have some sort of access to our sphere of knowledge or that they miraculously developed the same unit of measurement completely by chance. In either case the suspension of reality has been fractured and the reader is dragged back into the world they are trying to escape. To refer to ‘inches’ and ‘miles’ in a fantasy novel [...] suggests that either these fantasy characters have some sort of access to our sphere of knowledge or that they miraculously developed the same unit of measurement... How can this be fixed? The first and perhaps most obvious solution might be to do the same thing that fantasy authors do with languages, towns, cities, and countries: make one up! But if you are to create a system of measurement in your fantasy world then you are stuck with the exact opposite problem. It is not your fantastic characters that are in possession of inaccessible knowledge but your reader who has a lack of inherent knowledge about the fantasy world. To inform them of the length of an imaginary unit of measure you'll need to use units the reader can understand, units like ‘inches’ and ‘miles’, and once again that drops them back into the reality that you are trying to suspend. To inform them of the length of an imaginary unit of measure you'll need to use units the reader can understand, units like ‘inches’ and ‘miles’, and once again that drops them back into the reality that you are trying to suspend.

This allows the reader to remain in fantastic suspension while the narrator handles issues The second solution is a bit more challenging but, I believe, lets the reader immerse themselves more fully in the world and, more importantly, in the story. Instead of relying on a narrator to bridge the worlds, the author can look for common experiences between them that could conceivably be shared without any ‘leaking’ of information. Ancient civilizations demonstrate this concept superbly as they developed things like chairs and clothing and swords independently without any need to ‘leak’ information between themselves. ...the author can look for common experiences between [the worlds] So let us return to the problematic phrase about ‘inches’ and ‘miles’. With the right kind of narrator the units of measure used in the fantastic world can be directly translated to familiar units. Alternatively, the author might try to identify experiences common to both the fantasy characters and the reader. For example, to describe the height of buildings I have taken to comparing the distance to spear lengths. Spears, common across many cultures, usually reach a bit higher than the average person. A house that is “three spear lengths high” then becomes a description that would give both the reader and the characters in the fantastic world a good sense of its size. For longer distances, such as 30 miles, the author might express the distance in terms of time. If you believe that most people can walk about 10 miles in a day then to say that a group of characters walked for three days conveys a distance similar to 30 miles without needing to use a specific unit of measure. For example, to describe the height of buildings I have taken to comparing the distance to spear lengths. Of course, this is just one brief example of a ‘leaky world’ problem, but it illustrates a pitfall quite particular to fantasy which I believe should be vigorously avoided. Common phrases such as cliches are particularly prone to ‘leaking’ information and should either be avoided altogether, used very cautiously, or adapted to better suit the culture of the fantasy world. By crafting a narrative that brings the reader into a story with as few ‘leaks’ as possible we can convince them to leave reality behind and experience the wonder, the beauty, and the terror of our imagined worlds. By crafting a narrative that brings the reader into a story with as few ‘leaks’ as possible we can convince them to leave reality behind and experience the wonder, the beauty, and the terror of our imagined worlds. Early into the first draft of The Gatewatch I had a minor crisis of identity. Who was I to assume that I could write a book worth reading and did I recall enough proper grammar to pass for a 'real' writer? To quell my doubts I began devouring writing advice by respected authors while I pressed on with the story. Who was I to assume that I could write a book worth reading I first reread an excellent essay I encountered in university, George Orwell's Politics and the English Language. His pointed message renewed my determination to pursue and eliminate pretentious diction, meaningless words, and dying metaphors. As a writer of fantasy, a genre too often plagued by these particular issues, I found it necessary to thoroughly purge what I had written in my rough draft before proceeding with the story.

While discussing dialogue, Stephen King suggests that descriptors such as shouted, whispered, screamed, roared, wailed, moaned, and whimpered should be used extremely sparingly, if at all. Even worse are phrases like whispered quietly, screamed furiously, or moaned woefully. The reason, of course, is that if you have not made clear from the context of the conversation what the tone of the dialogue is then using a phrase like ‘he shouted angrily' is profanely lazy. King suggests instead that writers invest more energy describing their red-faced, tight-fisted, jaw-clenched characters leading up to the dialogue so that readers can infer their tone from context alone. Stephen King suggests that descriptors such as shouted, whispered, screamed, roared, wailed, I took this advice literally and removed any word for dialogue besides said from my rough draft. Though I meant it to be more of a writing exercise than a rule I soon found that my scenes pulsed with an energy that they lacked before. I swore from then on never to use a phrase such as 'he shouted angrily' or 'she whispered tenderly' and to this day I have not used any attribution other than said. I swore from then on never to use a phrase such as 'he shouted angrily' or 'she whispered tenderly' For anyone willing to accept the challenge of using only said for dialogue I feel compelled to offer some support. One area of knowledge that I had a decent intuition about but failed to study closely before adopting this rule was the science of body language. Facial expressions and body posture can do more to communicate a character’s state of mind than a paragraph stuffed full of emotive descriptors. Ekman's Six Basic Emotions (Credit: Adam Murphy) These traits are so consistent that psychologist Paul Ekman categorized expressive facial movements into six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. These expressions are performed unconsciously and are nearly universal. I believe as writers we can reverse-engineer this categorization to craft physical descriptions that are organic and intuitive for readers to interpret. I believe as writers we can reverse-engineer this categorization to craft physical descriptions For example, in a scene of courtly intrigue one might expect a line such as this: “Damned fool,” Darius snarled disgustedly. I hope you will agree that this line is particularly awful. The word snarled falls flat as it is a gross exaggeration; animals snarl but people do not. It is also confusing as a snarl is an expression of aggression in animals, not of disgust. As if all this was not enough to push this line into irredeemable mediocrity, the use of the word disgustedly shows that the author had neither the time nor the energy to show how Darius felt but instead cut a quick corner by stating it directly. The word 'snarled' falls flat as it is a gross exaggeration; animals snarl but people do not. It is also confusing as a snarl is an expression of aggression in animals, not of disgust. To rework this line I would first identify the basic emotion that the character is experiencing, in this case disgust. Disgust has been identified as one of the six basic emotions and is characterized by distinct positioning of the eyebrows, nose, and mouth. By utilizing these facts we could, perhaps, redeem the line as follows: Darius furled his brow and wrinkled his nose. “Damned fool,” he said. In this case the word used for dialogue attribution is not hijacked to reveal Darius’ state of mind; it simply does its job of identifying who is speaking. In fact, the actual word disgust does not appear in the text at all. Through the description of Darius’ face and our own experience with facial gestures we, as readers, know exactly how Darius is feeling without being whomped over the head with a direct description. Our imagination is allowed to fill in the emotional context, and that is a far more powerful tool than words on a page. In this case the word used for dialogue attribution is not hijacked to reveal Darius’ state of mind; Further, we can easily adjust this line to convey other emotions by altering Darius’ facial expressions. If instead of wrinkling his nose Darius flared his nostrils we would know that he is feeling anger (another one of the six basic emotions) instead of disgust. Again, if he had opened his mouth and raised his eyebrows we would infer that he is surprised instead of angry or disgusted. If instead of wrinkling his nose Darius flared his nostrils we would know that he is feeling anger Though it is sometimes necessary to use said to identify the speaker I would refine the line one step further by eliminating the dialogue attribution altogether and communicating the source of these words through their position on the page like this: Darius furled his brow and wrinkled his nose. “Damned fool.” Though some might disagree with this last step, I have taken to doing this whenever possible. By avoiding dialogue attributions other than said, and even using said only when necessary, I have been able to craft lively dialogue between characters that is not hindered or burdened by unnecessary descriptors. In other words, some things really are better left (un)said. For sage advice on the craft of writing Joshua recommends Stephen King's On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.

The advice I gave in Part I of Becoming a Resilient Writer went down pretty easy, maybe not ‘strawberry milkshake’ easy but certainly ‘spinach smoothie’ easy. Part II is full of suggestions that most will find about as palatable as shooting apple-cider vinegar straight. However, as a beneficiary of honest writing advice myself I feel compelled to pass these lessons on. "Clearly the message of resilience resonated with the wider writing community. " The first lesson on the second stage of my writing journey is this: view rejection as a personal victory. I am not kidding when I tell you that I literally jumped out of my chair and did a double fist-pump in the air when the notification of my first rejection popped up on my phone. I was elated. Why? Because I was rejected by a big publisher. That means they had considered it. For three seconds, three pages, or thirty minutes, it didn’t matter. And believe me when I say it was not the last rejection I received. If I had let those rejections knock me down a notch I’d be far enough underground to hit the water table by now. Whatever I felt, whether it was excitement, frustration, or fear, I threw into the tank as fuel to send out another query, to reach out to another author, or to push through another edit of my manuscript. So don’t let rejection burn you down; use it as rocket fuel instead and eventually you will achieve lift-off. "So don’t let rejection burn you down; use it as rocket fuel instead and eventually you will achieve lift-off. "

"That twenty five minutes which should have been spent crafting the final climactic scene will be squandered scrolling through the responses (or a depressing lack thereof) on your feed. Instances become patterns. Patterns become habits." The third piece of advice I have for writers who aspire to publish their work is this: start networking early and pay it forward whenever you can. There is an incredibly diverse and active community of writers, published and unpublished, who are working their fingers into nubby little stumps trying to get their next book finished and released. Recognize that the rush you get from someone sharing a post about your novel or commenting on an interview you were in is something of value that you can pass on to other people. Here’s the best part: it only costs you a bit of time and energy. And while some might say that time spent connecting with and encouraging other authors should be spent writing, your future publisher might disagree. After all, writing a book is only the beginning; your future publisher is part of the publishing industry and that means selling books. The professional support network you build will be instrumental in getting your book into the hands of fans all over the world. So do unto others as you’d hope they would do to you: send encouraging notes, cheer on their successes, and invest in your own community of author friends, publishing contacts, and future fans. "And while some might say that time spent connecting with and encouraging other authors should be spent writing, As I said in Becoming a Resilient Writer (Part I), not everything that works for me will work for you. But the creative potential within you will not be fully realized if you don’t have the resiliency to see your projects through. Stand firm, forge ahead, and write the story you were born to tell. For more on writing and resiliency Joshua suggests reading Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art.

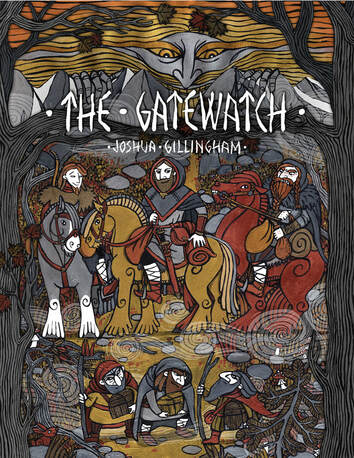

"as the northern realm of Noros came into clearer view and the main characters delved The three main characters, Torin, Bryn, and Grimsa, are inspired by the three central figures of Norse Mythology: Odin, Loki, and Thor. Other characters throughout the book reflect familiar Norse personalities in a much looser sense: Freya, Frigg, Heimdal, and the dwarven brothers Brokk & Eitri to name a few. Certain events, such as a drinking contest in an enormous mead hall, are directly based on specific myths, in that case Thor’s Journey to Utgard. Torin’s obsession with riddles (part of his Odin-like nature) culminates in a duel of riddles to the death with a giant king; this is inspired by scenes from The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek and from Vafþrúðnismál in the Poetic Edda. The epic poems recited in the book are structured around some of the poetic rules of drottkvaett, the ancient court meter of viking skalds; further, many treasure and place names are direct or close translations of Old Norse words. And, of course, the entire book centers around defending the human realm against giants and trolls which is a classic heroic task of both Norse gods and Viking heroes. "the entire book centers around defending the human realm against giants and trolls

"any readers who have had the pleasure of bathing in Iceland’s Blue Lagoon will recognize its influence on the underground baths visited by the characters in Gatewatch" Distinctly lacking in The Gatewatch are Viking longships and the northern sea because the story takes place high up in the mountains. This, of course, will be remedied in future sequels, the first of which is already well underway. For now, find the first three chapters on the website and stay up to date on publication details and future novels by joining The Gatewatch mailing list.

|

AuthorJoshua Gillingham is an author, editor, and game designer from Vancouver Island, Canada. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed